The Dawn of Drugs

How did it all begin? strangely, no doubt, in the morning of time and space on this planet.

How did it all begin? strangely, no doubt, in the morning of time and space on this planet.

Purposeful cultivation of drug plants is thought to have started during the neolithic period, somewhat after 7000 B.C. In most parts of the world. But the gathering of plants that do weird things to the mind had doubtless gone on for millennia. A fantasy about the discovery of Marijuana, one of the oldest cultivated species, can stand metaphorically for all the rest.

Some inquisitive cave dweller in his unceasing search for food, plucks the pungent flower tops and crams them in his mouth, crunching the seeds with mighty molars; an hour later he's wandering through the forest in a daze, trying to remember what happened. Or lightning strikes a tree, and the blaze spreads to a clump of hemp standing tall in the meadow; a curious Neantherthal sniffs the air, alert to the smoke and poised for flight. Instead he ends up rolling in the dirt bellowing owow, the first human word. repeat such an episode the world over, for invigorating coca, lysergic morning glories, musky opium, phosphorescent muschrooms, prickly thorn apple.

Or maybe humans learned about drugs from animals. Australian folklore has it that koalas are adicted to eucalyptus leaves, their only food, because the leaves have a genuine narcotic effect.

In Africa, where the ancestors of homo sapiens first evolved about three million years ago, the exhilarating effects of coffee were legendarily discovered by an Abyssian goatherd who noticed his flock prancing around the pasture after eating the fruit of that glossy green tree; a similar tale is told in Yemen about khat. The Indian Mongoose, when bitten by a cobra, crawls into the jungle to nibble mungo root as an antidote. Cows everywhere love locoweed; cats gobble catnip; reindeer munch muschrooms.

Rabbits prefer belladonna or wild lettuce; songbirds and mice thrive on hempseed; fish get knocked out by toxic plants that fall into water. Even elephants are passionately fond of certain palm fruits that produce a strongly intoxicating liquor and, in the words of a nineteenth-century explorer, "After eating it become quite tipsy, staggering about, playing huge antics, screaming so as to be heard mioles off and not seldom having tremendous fights."

However it happened, early humans learned to like drugs. But was it a drug that awakened the psyche to science? Is the difference between man and ape a crooked thumb, or something more: an imaginative spark lit up in the brain by a plant? Or the ability to value the effects of that plant, clinging to it through the eons, though it made them retch, collapse in the snow and run raving trough the underbush?

The flush of discovery gave way to a purposeful search for mind benders all over the globe. Mom and dad huddled around the fire, teaching the kids to get high, sketching plants on the blackened cave walls. It was the juice of certain plants that first proved so attractive: the ooze of bruized poppies, the bland unearthly creams of pounded fungi, the sticky resin of hops and hemp, the succulent syrups of grains and fruits, the ripe pulp of a thousand exotic roots and vegetables. Chewed, mashed, strained, ground up, gulped whole, raw, cooked, fermented, rotted, fresh, putrescent, fried, fricasseed, soouped, savored, spat out and shat out, picked off dungheaps and vines, stored in old baskets and pots, thrown in the fire, salved on the skin, poured in every orifice, the recepies were remembered and traded down trough generations. And archetypal memories of dead trips too: Don't eat that one, deary, it killed Aunt Goombak.

After centuries of experiment, a special breed evolved - the sorcerers, men and women who knew which dope to eat and which not to; when to eat it and when not to; which gods to thank and which to curse. The secrets of these doctors of dope have always been, at least in part, secrets of selection and technology. One didn't go to the medicine cabinet, one went to the field - and woe to the one who selected the wrong plant. Knowing how to make barley beer 10.000 years ago was as formidable as knowing how to make LSD today.

After centuries of experiment, a special breed evolved - the sorcerers, men and women who knew which dope to eat and which not to; when to eat it and when not to; which gods to thank and which to curse. The secrets of these doctors of dope have always been, at least in part, secrets of selection and technology. One didn't go to the medicine cabinet, one went to the field - and woe to the one who selected the wrong plant. Knowing how to make barley beer 10.000 years ago was as formidable as knowing how to make LSD today.

Some secrets were so closely guarded that they remain classic mysteries. What was the tree of life, which gave knowledge of good and evil?

What was Homer's nepenthes pharmacon, which drowned all sorrows? Did the citizens of Sumer use opium or hashish to drug the courtiers buried alive with their king or queen, or was it merely wine? What were soma and hoama, beloved of the Aryans of India and Persia? What did the Taoist magicians of China cook up in alchemical pots to produce devine do-nothing euphoria? And in the New World, richer by far than the Old in hallucinogens, what exactly did they smoke in peace pipes and corn husks and snort with nose tubes and spatulas? Why did Inca priests call bright star Spica in Virgo "Mama Coca" - did they think it came from there? At what premeval age did somebody learn to eat the nauseating cactus with its tender dinosaur skin, or mash the barky creepers and the hairy-tendriled vine? Wo first imagined that a funky fungus could open up a vision higher than the sacred mountains of the gods? the most sophisticated tools of modern science have left such questions unresolved; perhaps they must always remain shadows in the mystic past.

To watch drug history unfold is to tap into the most profound of human senses: déja vu - it has all happened before, it will all happen again.

Drug-induced distortions of time's space allow the paticipant to slip effortlessly from eon to eon, from scene to cosmic scene. And maybe it is this highlightning of ancestoral memory, this sense of timeless mythology produced by the drugs themselves, that best illuminates the history of drugs through the ages.

We have learned much about getting high since humanity first awoke on earth, and we are still learning. The first precept of sorcery - selectivity based on experienced harm or helpfulness - is precisely the technique employed by modern scientists to test a new drug for safety. Some of the earlyest known examples of drug use illustrate this. carbon dating of rock-shelter sites in Texas and Mexico confirms that halucinogenic red mescal beans were used over 10.000 years ago by prehistoric buffalo hunters. These scarlet seeds are highly toxic and can be fatal. When someone found out that peyote offered more spectacular visions with less danger, the cactus was used instead of the legume. yet mescal beans still adorn the robes of Native American Church officials in commemoration of that ancient experience.

The next advancement of drug science was the move from eating whatever plant was handy to manufacturing special preparations. A battered bit of pottery is all that remains of perhaps the oldest such potion on earth - plain, homely beer. A beaker with a sieve at the bottom and strawlike tubes on its outer edge has turned up in levels dated about 6500 B.C. in Catal Hújúk. Turkey.

Scholars believe that this and similar sieve-pots in predynastic Egypt represent the fact that some Neolithic wizard learned to crush the barley he'd gathered, push it through the strainer, let it ferment a while and drink the yeasty, protein-rich mess that would transport him into unacustomed mind. B y 4500 B.C., according to Dr. Richard H. Blum, Egyptians "had learned to maximize fermentation and alcoholic content by malting their grain... And all southwestern Asian cultures had beer as a liquid staple."

western civilisation's suspicious attitude toward drugs began in a blearly bath of barley brew. Beer and bread were daily wages in Sumer, Babilon and Egypt. "Drink not beer to excess!" the workers who bild the pyramids were warned. "You speak stupidly and cannot remember he words that come out of your mouth. You fall and break your limbs, and no one reaches out a hand to you. Your drining friends stand up and say, 'Away with his drunk!' And if someone comes asking after you, they find you lying on the ground like a child."

western civilisation's suspicious attitude toward drugs began in a blearly bath of barley brew. Beer and bread were daily wages in Sumer, Babilon and Egypt. "Drink not beer to excess!" the workers who bild the pyramids were warned. "You speak stupidly and cannot remember he words that come out of your mouth. You fall and break your limbs, and no one reaches out a hand to you. Your drining friends stand up and say, 'Away with his drunk!' And if someone comes asking after you, they find you lying on the ground like a child."

Though beer was the brew of the toiling masses, wine was the elixer of aristocracy. Egyptian wine feasts were legendary, for reasons visible on New Kingdom paintings (ca. 1580 B.C.). Splenditly gowned women andmen wearing costly jewelry sit comfortably sniffing lotuses while servants offer them perfumes, ointment, bowls of wine and fruit. Over in the corner rests a wine vat wreathed in plumes, taller than the naked dancing girls who twist and turn, clapping their hands to the music of an exotic-looking female band. It was easy to overindulge, as another picture discribed by Adolf Erman shows:"One lady squats miserably on the ground, her robe slips down from her shoulder, the old attendant is summoned hastily, but alas! she comes too late." A hangover cure was needed. The earliest is recorded on a Mesopotamian stele and incidentally illustrates another scientific advance: the mixing of several drugs into one magic medicine. "If man takes strong wine, his head is affected and he forgets his worlds; his speech becomes confused, his mind wanders, his eyes have a glazed expression. To cure him, take licorice, beans, oleander [and eight unidentified substances], compounded with oil and wine, before the approach of the goddess Gula [sunset]. In the morning, before sunrise and before anyone has kissed him, let him drink it and he will recover." Ninevite tablets of about 2300 B.C. allude to popular taverns called bit sacari, and the eye-for-an-eye Code of hammurabi a few centuries later perscribes harsh penalties for misconduct in these bars.

Beers and wines flowed freely aroound the world. Genesis asserts that Noah, the first vineyard keeper, was a shameless drunk. Africans made palm toddy, millet and sorghum beer; Tibetans brewed chang from barley; Peruvians, chica from corn; Mexicans, pulgue from agave. A legend of prehistoric China says two royal astronomers were executed for being so wasted that hey failed to notice an eclipse; another has it that the inventor of rice wine was banished. Norsemen adored mead, the sweet honey nectar that fueled the exploits of Odin, Freya and Thor. Of all ancient peooples, the Greeks were the most cautious about wine, always mixng it with water and deploring the barbaric practise of drinking it neat.

Herodotus describes warm wine (laced with human blood) and wild weed among the Scyntians, and he says the hated Persians made all major decisions stone drunk and reconsidered any decision made sober when they were drunk again.

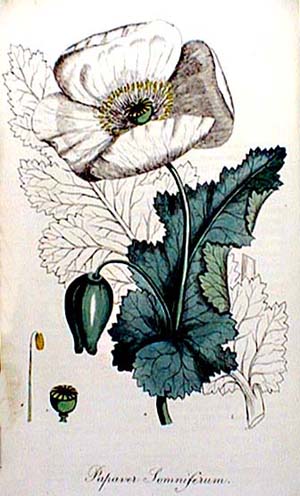

As Plutarch intimates, wine as considered a medicine. It was also the fluid in which most herbal remedies were taken. Egyptian medical papyri list about 200 drugs, including onions, figs, garlic, anise, juniper berries and poppy and sesame seeds, washed down in wine, beer, oil or honey. There was an astonishing early trade in spices and drugs. Cassia and cinnamon, used in embalming, came from China and Southeast Azia; aromatics of myrrh, balsm and frankincense, from Arabia and India. Silphium, the celebrated panacea plant of Greece, grew in Lybia, and exports were so heavy that it became exstinct in the first century A.D. The most famous prescripton of Egypt was a remedy for children's crying:"Shepen, the grains of the shepen-plant, mixed with excretions of flies on the wall, strained to a pulp, passed through a sieve and administered on four consecutive days, will stop their crying at once." If shepen was opium, as most scholars think, the cure would indeed have been effective, with or without fly specks.

Mysterious nepenthes in the Odyssey may be related to this. When Telemachus visited Sparta, beautiful "Helen, daughter of Zeus, poured into the wine they were drinking a drug, nepenthes, which lulled all pain and gave forgetfulness of grief. Those who had drunk this mixture would not shed a tear the whole day long, even if their mother or father were dead, even if a brother or beloved son had been slaughtered by an enemy's weapons before their eyes." Helen had obtained the drug from Polydamna, wife of Thon, in Egypt, "that fertile land of many drugs, some beneficial, some deadly, where everyone knows medicine." the identity of nepenthes has puzzled people ever since. Theophrastus said it was probably a frigment of the poet's imagination; Dioscorides guessed it was a mixture of henbane and opium; many have thought it was hashish; and Louis Lewin curtly gave the modern view, : There is only one substance in the world capable of acting in this way, and that is opium."

What the ancients knew about opium gives us a quick panorama of the developing twin sciences, pharmacy and toxicology. Papaver Somniferum pods and seeds have been unearthed in Neolithic sites all over Europe. Capsule-shaped vases, pins and amultes have been found in Egypt, Greece and Cyprus, while a Minoan poppy goddess statue, crowned with a tiara of incised poppy capsules (ca. 1300 B.C.) has turned up in Crete. Identification of the words Hul Gil (variously translated as 'joy plant' or 'stink cucumber') on Assyrian medical tablets as opium is conjectural but provocative. At last, in the fifth century B.C., Hippocrates, father of Greek medicine, states unequivocally that poppy juice is used as a painkiller in therapy.

What the ancients knew about opium gives us a quick panorama of the developing twin sciences, pharmacy and toxicology. Papaver Somniferum pods and seeds have been unearthed in Neolithic sites all over Europe. Capsule-shaped vases, pins and amultes have been found in Egypt, Greece and Cyprus, while a Minoan poppy goddess statue, crowned with a tiara of incised poppy capsules (ca. 1300 B.C.) has turned up in Crete. Identification of the words Hul Gil (variously translated as 'joy plant' or 'stink cucumber') on Assyrian medical tablets as opium is conjectural but provocative. At last, in the fifth century B.C., Hippocrates, father of Greek medicine, states unequivocally that poppy juice is used as a painkiller in therapy.

Aristotle, whose philosophic speculations on animals and plants founded biology, mentions the poppy as a "hypnotic" (from Hypnos, god of sleep). He left his library to his pupil Theophrastus, who carried on the Dr. Dope tradition with a massive Enquiery into Plants that gives perhaps the earlyest specific mention of incising the poppy to obtain opium. Aristotle's other famous pupil, Alexander the Great, took trained herbalists with him to Persia and India who returned with much knowledge of Asian plants, though Alexander himself died of a fever after a bout of heavy drinking in Babylon. Soon thereafter, Greek schools were founded in Syria and Alexandria that promoted the flow of pharmacology and ultimately preserved Aristotelian teachings in Arabic.

thus there developed a fund for information available, in addition to folklore provided by herb pickers (rhizotomoi) and drug dealers (pharmakopolai). Moreover, there was state support for botanical research, especially from rulers fearful of being poisoned. Mithridates VI, King of Pontus in Azia Minor (120-63 B.C.) described all the medicinal plants of his kingdom himself and employed a rhizotomist named Krateuas as his personal physician. Together, they gained the reputation of knowing more about poisons than anyone else in the world; the king lent his name to mithridatum, the most renowned antidote of the age, and his herbalist provided the most lifelike pictures of plants ever drawn at the time. Among them was a poppy, now christened papaver dubium, which yields opium.

So sophisticated was the art of poisoning that occasionally the precaution of hiring slaves as food tasters didn't even work. Tacitus tells us that when Nero assumed the Roman throne in D.D. 54, he hired a woman under sentence for poisoning to prepare a fast-acting toxin to slip into his brother Britannicus's wine, but they had to figure out a way to fool the test taster. Remembering that Britannicus liked his wine heated, Nero presented im with a cupful that the slave pronounced too hot to drink. The poison was then poured in with some cold water, and the unsuspected britannicus downed the wine in a gulp. A few seconds later Nero's claim to the throne was undisputed - except by his mother, a celebrated poisoner herself.

The greatest authority on drugs in the ancient Mediterranean was Dioscorides, a surgeon born in Asia Minor who traveled widely with Nero's army collecting information. He compiled a masterwork, the Materia Medica, which included about a thousand vegetal, animal and mineral drugs. Of these, some 600 were plants (about a hundred more than in Theophrastus and about 450 more than were known to Hippocrates). Pictures of many of these species, some based on Krateuas, were preserved in a Byzantine codex of A.D. 512 and became the basis for botanical illustrations for the next thousand years. Dioscorides's descriptions of drugs and their effects, though brief, were far superior to any that had come before. Among the plants exalted by Dioscorides are cannabis, opium, white and black hellebore, henbane, aloes, hemlock, aconite, Syrian rue, sweet flag, onions, juniper and a great many flowers and spices. His compendium had immediate impact on Galen and Pliny and the later great herbalists. Clear trough the height of the Rainessance, De Materia Medica was regarded as the almost infallible authority. Dioscorides, incidentally, first used the word anesthesia in its modern medical sense. And Dioscorides's approach to pharmacy lives on in modern texts such as the Merck Index, which now includes 42.000 chemicals and drugs, laid out in the easy-reference alphabetical order invented by this studious army doctor almost 20 centuries ago.

The Merck Manual, on the other hand, follows a pattern set by the Egyptian papyri of listing various diseases, with appropriate prescriptions for each. This is also the style of the Ayurvedic medical teachings of India, which are much broader in scope. Indian medicine began in Vedic religious and magical texts of the second millennium B.C. and advanced into encyclopedias attributed to doctors Charaka and Sushruta.

"There is no substance in the world that is not medicine." Charaka proclaimed, and proved the point, employing thousands of drugs in perscriptions for every conceivable disease.

Charaka records the first drugs conference in the seventh century B.C., and it is likely that his work is a compilation of all the plant lore of India at that time. Among the innovations in Charaka are recognition of about 80 varieties of wine, treating mental patients in padded cells, mantra chanting to make drugs more effective, intensive training of dancing girls as poisoners, careful notes on drug storage and smoking aromatic herbs through reed pipes off cloth sigars: in case of tubercular cough, for example, Charaka recommended that "the patient may smoke the sigar rolled with the cloth of linseed, impregnated with red arsenic, palas, wild carrot, bamboo manna and dry ginger. After smoking, the patient may drink the juice of sugar cane or gur water."

the surgeon Sushruta listed over 760 plant drugs, including anesthetics, poisons, narcotics and spices. licorice and pepper were his favorite medicines; mangoes, myrobolans, peppers and datura were his aphrodisiacs of choise. He was the world's first plastic surgeon, rebuilding noses cut off as punishment for adultery. Sushruta fumigated operating rooms with aromatic herbs and used deadly nightshade, indian hemp and datura to induce stupor. Snakeroot (Rauwolfia Serpentina), from which modern chemists extract the tranquilizer reserpine, was perscribed for fever, snakebite, cholera, difficult childbirth and "moon madness" or lunacy.

the origin of Chinese pharmacology is ascribed to the mythical emperor Shen Nung. Tradition has it that he tested a hundred drugs on himself and, because he could make his system transparant at will (what a nice metaphor for seeing into oneself with drugs), he was able to observe their actions ant take an antidote if necessary. He was thus able to classify them: "superior" drugs were nonpoisonous and rejuvenating: "medium" were somewhat toxic, depending on dose; and "inferior" were poisonous, but useful in certain ilnesses. The first Chinese Pharmacopoeia (pen ts'ao) followed this scheme and was attributed to Shen Nung, though it was actually compiled by scholars of the Han dynasty (206 B.C. - A.D. 220). it listed 365 therapeutic herbs - one for every day of the year - including hemp, ephedra, rhubarb, licorice, sesame, ginger, cassia, cinnamon and the marvelous aphrodisiac and cure-all, ginseng. Like mandrake in the west, the more ginseng root resembled the human body, the more effective it was thought to be.

the origin of Chinese pharmacology is ascribed to the mythical emperor Shen Nung. Tradition has it that he tested a hundred drugs on himself and, because he could make his system transparant at will (what a nice metaphor for seeing into oneself with drugs), he was able to observe their actions ant take an antidote if necessary. He was thus able to classify them: "superior" drugs were nonpoisonous and rejuvenating: "medium" were somewhat toxic, depending on dose; and "inferior" were poisonous, but useful in certain ilnesses. The first Chinese Pharmacopoeia (pen ts'ao) followed this scheme and was attributed to Shen Nung, though it was actually compiled by scholars of the Han dynasty (206 B.C. - A.D. 220). it listed 365 therapeutic herbs - one for every day of the year - including hemp, ephedra, rhubarb, licorice, sesame, ginger, cassia, cinnamon and the marvelous aphrodisiac and cure-all, ginseng. Like mandrake in the west, the more ginseng root resembled the human body, the more effective it was thought to be.

Effervescent powders were administered in wine, and one of these - ma fei san, probably a cannabis concoction - was the earliest anesthetic of China. It was invented by the revered surgeon Hua T'o at the end of the Han dynasty for cases where acupuncture, moxa or salves didn't work and surgery was required. Hua employed few drugs otherwise but was so knowledgeable about them that a ruler fearful of being poisoned order him put to death - ending Chinese surgery for hundreds of years. Before he went, however, Hua had trained his students in exercises ("The frolics of five animals") to promote good health; these were the forerunners of t'ai chi ch'uan and all the martial arts.

Soon taoist magicians were seeking immortality with kung fu, health food and a host of drugs. Undoubtly many of them were charlatans - but the greatest, an alchemist named Ko Hung (ca A.D. 300) was not. Ko allegedly succeeded in transforming herbs and precious metals into an elixir of immortality with cinnabar, and it is said that when he died his corps felt incredibly light, as if the schrouds had been emptied of the body. Ko formulated rules to strengthen breathing and blood circulation with tonics and special diets. He emphasized the need for simple, inexpensive cures for common ailments, such as his perscription for asthma - a compound of ephedra, cinnamon, licorice and powdered apricot kernels.

Similar folk remedies were spread far and wide by Buddhist monks who wandered slowly from India to China, japan and Southeast Asia gathering herbs. Tea was legendarily discovered by Bodhidharma, the founder of Ch'an (Zen) Buddhism, who cut off his eyelids after falling asleep while meditating; where the bloody eyelids fell, the tea plant sprang up, from which Bodhidharma made a drink that would keep him awake. (Similar stories abound in Arabia about Sufi monks with coffee.) Herbal teas rapidly took their place beside ginseng and wines in Chinese pharmacy and remain an important part of medicine by China's "barefoot doctors" today.

While European science was dozing through the Dark Ages, Arabic and Chinese pharmacology were vital and bright; and when these two traditions met with Hindu medicine over the silk routes, every doctor and doper in the known world was intrigued. Medieval Europe became a continent of fabulous hearsay, a seething cauldron of magical secrets and rumors from Arabia, India and Cathay. professional medicine was barely removed from sorcery, and in fact the witches may have known more about drugs than the doctors. Other than alcohol, the major anesthetic was was the spongia somnifera, which consisted of opium, mandrake, mulberry, hemlock, wood ivy, dock and lettuce juice soaked on a sponge. Witches brews had about the same ingredients, with added solanaceous hallucinogens.

Famine, smallpox and plague swept trough rat-infested towns, whose starving citizens reluctantly ate diseased rye and wheat crusts, which gave them ergotism (St Anthony's fire). A mania accompanied by open sores and gangrene. The sick and dying sought refuge in the church, where pharmacy meant picking garden herbs and medicines meant faith. A common perscription for blindness was to swallow a live worm whole while reciting the lord's prayer; bleeding, by leeching and cupping, was the cure for bubonic plague. The favorite recreational drugs (except among witches) were still mead, beer and wine.

Official learning centered in the monestaries where scribes laboriously copied out crumbling parchments by hand. Ultimately, it was this painstaking "copyright" that brought Europe out of the dark, for by this means Arabic science, translated into latin, slowly seeped into Europe.

And what splendors the genius of Muslim pharmacology offered the world! Oriental scientist-philosophers preserved the Greek and Roman tradition and crowned it with the glories of Asian drug lore. Innovations arrived from deep within Africa, up throuogh Salerno and Gordova, across Persia from India and T'ang Dynasy China as fast as Arabian stallions could carry them.

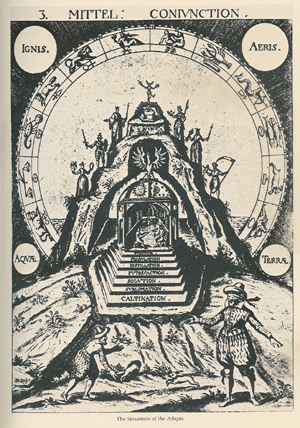

What began as mysicism became true science. the alchemist Geber (A.D. 750) developed Dioscorides's herbal into an esteemed dissertion on poisons, adding electuaries of bhang, ergot, nux vomica, mercury, arsenic and cinnabar. He tried to find the "philosopher's stone" by which base metals could be transmuted into gold, and in the process invented nitric acid, sulfuric acid and the distillation of alcohol. Europeans regarded his cryptic writings as mere "gibberish" - the origin of that term - until they discovered the pleasures of his aqua vitae in whiskey, brandy and gin.

Rhazes of Bagdad (A.D. 900) well understood the pathology of smallpox and other terrifying pestilences; yet seven centuries later, European doctors were still wearing bird maskes to fend off plagues. The Persian visionary Avicenna (980-1037) turned time-honored mythology into clinical research by trying anesthetics on himself, recording his experiments in a bulging treatise on drugs; he is said to have died of an opium overdose as a result. Ibn Beitar in the thirteenth century expanded Avicenna's work into the most extensive muslim materia medica, with the therapeutic applications of about 1400 drugs. Europe slowly became consious of these advantages. Chaucer, for one, was familiar with "Avicenna's long ralation/Concerning poison and its operation" and the works of other Arabic dope doctors mentioned in The Canterbury Tales.

The rich muslim tradition absorbed kola and kanna from Africa, khat from Yemen, datura and betel from India, nutmeg en cloves from the Spice Islands, and in return gave the world opium, hashish, coffee and alcohol. Mandrake, myrrh, theriac, funugreek, aconite, cardamom and many other exotic drugs well known in ASrabia found their way into Chinese medicine by the eleventh century; distilled alcohol by the thirteenth. The Mongol warlords such as Kublai Khan, who ruled China when Marco Polo visited in the thirteenth century, were fierce drinkers and dopers, and their heirs, the Moghul emperors of India, cultivated opium and pot and made their use common courtly practise. Tantric adepts used wine, spiced meat and marijuana milkshakes in eleborate erotic religious ceremonies. The T'ang, Sung, Yuan (Mongol) and Ming dynasties of China gathered all the drug information of Asia in magnificent pharmacopoeias, culminating in the Pen Ts'ao Kang Mu of Li Shih-chen in the sixteenth century, which took 27 years to complete and gave 8.160 recepies for 1.871 different substances. Europe, meanwhile, was just finding out about coffee - and trying to ban it as some satan's swill of the infidels.

The rich muslim tradition absorbed kola and kanna from Africa, khat from Yemen, datura and betel from India, nutmeg en cloves from the Spice Islands, and in return gave the world opium, hashish, coffee and alcohol. Mandrake, myrrh, theriac, funugreek, aconite, cardamom and many other exotic drugs well known in ASrabia found their way into Chinese medicine by the eleventh century; distilled alcohol by the thirteenth. The Mongol warlords such as Kublai Khan, who ruled China when Marco Polo visited in the thirteenth century, were fierce drinkers and dopers, and their heirs, the Moghul emperors of India, cultivated opium and pot and made their use common courtly practise. Tantric adepts used wine, spiced meat and marijuana milkshakes in eleborate erotic religious ceremonies. The T'ang, Sung, Yuan (Mongol) and Ming dynasties of China gathered all the drug information of Asia in magnificent pharmacopoeias, culminating in the Pen Ts'ao Kang Mu of Li Shih-chen in the sixteenth century, which took 27 years to complete and gave 8.160 recepies for 1.871 different substances. Europe, meanwhile, was just finding out about coffee - and trying to ban it as some satan's swill of the infidels.

When Marco Polo returned to inform the good citizens of Venice about ambergris, musk, spice wine, camphor, saltpeter, cloves, peppers, cubebs, coconuts, ginger, condensed milk, crocodile gall, spikenard, nutmeg and other treasured medicines - not to mention spaghetti, gunpowder, asbestos, paper money and the Assasins - they dismissed him as a crackpot teller of tales. but the enlightening influence of the great Muslim information influx was powerful indeed. Valerius Cordus (1514-44) revised Dioscorides to give Europe its first reaal pharmacopoeia and transformed Geber's sulfuric acid into sweet oil of vitriol, later called ether. his contemporary, the mad Swiss doctor Paracelsus, tossed Avicenna's books into the fire as a protest against hidebound reliance on the past, but craftily retained the recepies for ether and opium tincture (laudanum) for personal use.

The Arabs learned paper making from the Chinese and exported cotton paper throughout the mediterranean. In Spain hemp and flax fields flourished, and by the thirteenth century the resulting paper was widely used in Castile. From there it was just a hop over the Pyrinees to France, then to Germany where in 1454 Johannes Gutenberg printed a bible with moveable type. Suddenly the new technology made it possible to print herbals for wide dissemination of drug information, instead of relying on rumor and musty old manuscripts.

And so came the Rainessance - a rebirth of learning in a Europe weary of lethal epidemics and fruitless cruisades. Experience spplanted rumor with hundreds of drug plants. In 1542, Historia Stirpium appeared, scolding scholars for their ignorance, summarizing a tthousand years of information about native and foreign plants and providing stunning new woodcut illustrations of many of them. Fuchs also included some American plants, such as Indian corn. The Age of Discovery was in full bloom.

Instead of gold and spices, Columbus had returned from the New World with news of tobacco and corn and hallucinogenic snuffs (the DMT containing cohoba of the Antilles). Suddenly a whole new continent of drug plants was open for exploration - and exploitation.

Great was the explorer's astonishment when it dawned on them that this continent was not the Indies of their dreams, but a strange new land. When Amerigo Vespucci reached the island of Margarita off the coast of Venezuela in 1499, instead of silk-clad mandarins drinking tea he found loinclothed natives shewing coca: "They were very brutish in appearance and behavior, and their cheeks bulged with the leaves of a certain green herb which they chewed like cattle, so that they could hardly speak....They did this frequently, a little at the time; and the thing seemed wondrous to us, for we could not understand the secret, or with what object they did it." Little did Vespucci know that he had stumbled on a sacred tradition stretching back 4000 years; but he did understand he wasn't in Cathay.

When Pizarro charged into Peru in 1532, he was offered sparkling chicha (maize beer) in golden goblets. He responded by seizing the Lord of the Incas, ransoming him for a roomful of gold, killing him and then melting down the gleaming Temple of the Sun, adorned with priceless gold models of coca springs. Inquisition priests spurned the Devine Plant of the Incas as a devil's weed but fed it to the conquered tribes to stimulate their forced labor in the mines. Though Monardes of Ceville and others commented on coca's amazing stimulative powers, it was not until the nineteenth century that Europeans paid much attention to the drug.

When Cortes took old Mexico, cutting a swath on horseback trough the greatest psychedelic empire the world has ever known, he asked for gold, "as a specific remedy for a disease of the heart" that Europeans felt. Montezuma showered him with it and proudly displayed huge gardens of medicinal plants as well. He offered the conquistadors "food of the gods" - frothy chocolate, tobacco reed cigarettes and pulque. The hospitable emperor commanded his sorcerers to make certain sacraments, dooubtless including magic mushrooms, peyote, morning glory seeds and sinicuichi, the auditory hallucinogen. Cortes refused these as "bewitched food" and went on to slaughter 60.000 or more Aztecs. Soon after, Coronado led an expedition north in search of the seven cities of gold. About all he found was the Los Angeles basis, where he noted that the smoke from the campfires never seemed to rise and the natives drank datura to make themselves clairvoyant. The sacred psychedelics of Mexico and the southwest were driven underground, on pain of death.

All except two, that is. Cortes sent seeds of cacao back to the Infanta of Spain, and soon noblewomen were swigging hot chocolate in church. And tobacco - was it psychedelic? It was the wonder drug of America, more widely used than any other, often mixed with other plants. Mild Nicotiniana tabacum was snorted as snuff and drunk as juice from mexico to Chile. But in North America, harsher species (N. rustica, attenuata, bigelovii) were used ceremonially, and the earlyest reports make it sound hallucinogenic: medicine-men going into trances, braves chortling over two-foot-long cilinders of weed, whole tribes sucking pipe and dancing in glorious frenzy, perhaps due to the other drugs smoked with it. But even in processed commercial tobaccos, chemists have discovered harmala alkaloids closely related to those in Yage, the Amazon visionary vine. We still have much to learn about these sacred plants.

William Emboden points out that "within a few decades there were more Spaniards converted to smoking than indians converted to Christianity." and the same holds true for the British, French and Dutch. Shortly after Sir Walter Raleigh brought pipes, tobacco and an Indian back to London, King james issued a fiery "Counterbase to tobacco" (1604) - which detered his loyal subjects not a whit. Tobacco became big business in Virginia, and colonists continued foraging for other drugs. A troop of soldiers stationed at jamestown cooked up some datura in 1676 and were so startled by its bizarre effects that it has been popularly known as "Jimson weed" (from "Jamestown") ever since.

Drug traffic was the mainstay of mercantilism. Tobacco from the west and coffee from the east conquered Europe in the seventeenth century. Smoke-filled coffeehouses served as centers of shipping and trade, as gossipy listening posts on the world. Modern insurance, the novel as a literary form, and august scientific institutions (for example, the British Royal Academy) were all hatched in coffeehouses. Daring plots of international intrigue spread coffee, tea and tobacco around the globe, and drugs became political forces and symbols. American colonists signaled their contempt for "taxation without representation" by dumping british tea in Boston harbor (1773), and soon you could tell which side of a revolution people were on by what they served you for breakfast. Drugs were the key ingredient in the "triangle trades" - rum, slaves and molasses in the West Indies, and opium, tea and silk in Asia. Laudanum, an opium tincture, was especially prized as medicine. The seventeenth-century physician thomas Sydenham prescribed it so frequently that he was called Dr. Opiates. hemp was planted around the world as a source for fiber but African slaves (and, later, indentured Hindu servants) brought to the New world a better use for it. The British East India Company sent thousands of adventurers abroad. Tobacco and opium smoking were forced on China. Leading to nineteenth-century "Opium wars." The Asians lost, a fact the British victors smugly called "opening the doors of China."

So many drug plants flowed into Europe that science and technology accelerated at a maddening pace. The Swedish royal botanist Carl Linnaeus invented genus-and-species classification to bring some order out of this chaos. He also grew marijuana on his window sill to confirm the sexuality of plants, which the monk Gregor Mendel later elevated to the science of genetics. Protochemists such as the eighteenth century's "Marquis of Outrage" experimented with a new alchemy based on Cordus and Paracelsus - the extradiction of crude drugs in alcoholic tinctures.

Trying to find a foothold from which to wrest India from the British, Napoleon led his troops and a contingent of scientific observers into Egypt in 1798. There, a whole army of Frenchmen turned on with hashish. French doctors in North Africa learned about the medical value of cannabis, and J.J. Moreau de Tours invented modern psychopharmacology and psychotomimetic drug treatment with studies on datura and hashish (1845). India was the choisest assignment for young British officers and many, like Robert Clive, first governor of Bengal, became opium addicts. A bright young surgeon, William B. O'Shaughnessy, introduced cannabis to western medicine (1839) and the telegraph to India.

Trying to find a foothold from which to wrest India from the British, Napoleon led his troops and a contingent of scientific observers into Egypt in 1798. There, a whole army of Frenchmen turned on with hashish. French doctors in North Africa learned about the medical value of cannabis, and J.J. Moreau de Tours invented modern psychopharmacology and psychotomimetic drug treatment with studies on datura and hashish (1845). India was the choisest assignment for young British officers and many, like Robert Clive, first governor of Bengal, became opium addicts. A bright young surgeon, William B. O'Shaughnessy, introduced cannabis to western medicine (1839) and the telegraph to India.

Questions were put in parliament about opium and cannabis, culminating in the first massive modern government investigations of drugs (for example, the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission report in 1898). Meanwhile, scholars busied themselves studying the Vedas and discovered that their ancestors were linked to the vast Indo-European language family in ages long past.

Preparation of crude drugs advanced the procedures of analytic chemistry enough so that in 1806 a German pharmacist, F.W.A. Sertürner, was able to extract an alkaloid from opium that he named morphine, in honor of Morpheus, the Roman god of dreams. this ushered in the great nineteenth-century era of alkaloid toxicology. caventou and Pelletier in Paris isolated strychnine from nux vomica, quinine from cinchona, caffeine from coffee; others followed with atropine from belladonna, coniine from hemlock and hyoscyamine from henbane. The availability of pure alkoids put pharmacology on a firm footing by allowing close scrutiny of dose-effect relationships, elucidated in François Magendie's Formulaire of 1821, the granddaddy of the psysicians' Desk Reference.

Soon youtful explorers were scouring he planet in search of more medicines. Richard Spruce plunged into the Amazon and, in an uncanny burst of foresight, collected stems of yagé (ayahuasca, caapi) for chemical analysis. Had anyone bothered to analize them, he would have realized that quite unrelateed Old and New World species can contain the same chemicals and the science of chemotaxonomy that Spruce foresaw would have been born. Not until 70 years later did chemists recognize that 'telepathine' from the Amazon vine was the same as the harmine from Dioscorides's old, familiar Syrian rue. As it was, Spruce's specimens served another purpose. Richard Evan Schultes of Harvard had them analized in 1969 and showed the amazing longevity of these hallucinogens: they were as active as if the material had been collected yesterday.

meanwhile, the Amazon spawned another scientific revelation. Naturalist Alfred R. Wallace collected plants, butterflies and beasts in the same teeming jungles and Charles Darwin did likewise on the voyage of the Beagle. Both read Malthus's Essay on Human Population and independendly hit on the principles of natural selection, which have become the basis of modern biology. "Natural selection could only have endowed savage man with a brain a few degrees superior to that of an ape, whereas he actually possesses one very little inferior to that of a philosopher," Wallace wrote, seeing very clearly that the slightest alteration in consciousness could wreak profound changes in the species". "With our advent there had come into existence a being in whom that subtle force we term 'mind' became of far more importance than mere bodily structure."

meanwhile, the Amazon spawned another scientific revelation. Naturalist Alfred R. Wallace collected plants, butterflies and beasts in the same teeming jungles and Charles Darwin did likewise on the voyage of the Beagle. Both read Malthus's Essay on Human Population and independendly hit on the principles of natural selection, which have become the basis of modern biology. "Natural selection could only have endowed savage man with a brain a few degrees superior to that of an ape, whereas he actually possesses one very little inferior to that of a philosopher," Wallace wrote, seeing very clearly that the slightest alteration in consciousness could wreak profound changes in the species". "With our advent there had come into existence a being in whom that subtle force we term 'mind' became of far more importance than mere bodily structure."

Inevitably, each new drug discovery was accompanied by a flurry of popular use. Thomas De Quincey founded modern dope literature with his Confessions of an English Opium eater (1821) as a direct result of his experiences with Laudanum, which he had taken for face and stomach pains. There were, of course, no laws against narcotics, and De Quincey himself noted that "the number of amateur opium-eaters (as I may term them) was, at this time, immense." Not only did poets Coleridge, Crabbe and Thompson indulge; there were als thousands of working people - cottonmillers, housewives, sweatshop kids - who nightly drowned their sorrows in gin and laudanum and daily interspersed their hours of drudgery with coffee breaks. The international influence of De Quincey's book was enormous. Alfred de Musset and Charles Baudelaire published translations of De Quincey, freely adapting the text to include their own experiences with wine, hashish and opium. Most of the great French Romantics observed or took part in the "Club des Haschichins" founded by Théophile Gautier, and Beaudelaire's eloquent Les Paradis Artificiels (1860) assured him a prominent place among he classic authors of drug literature. Meanwhile, in Schenectady, New York, a Union College undergrad named fitz Hugh Ludlow read De Quincey avidly, experimented with all the drugs on the local apothecary's shelf and penned America's first great compendium of recreational drug use, The Hasheesh Eater (1857).

But the worldwide polydrug subculture of a hundred years ago was still centered in the ancient search for anesthetics. Since the Dark Ages, almost the only painkillers available for surgery were mandrake, opium, belladonna and booze - hardly effective in stilling the screams of patients strapped in the horror chambers called operating rooms. True, Valerius Cordus's sweet oil of vitriol (ether) was used occasionally during the eighteenth century, but it took further advantages in technology to make it really practical. Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen and nitrous oxide (1772), and Sir Humphry davy experimented with nitrious oxide at Dr. Thomas Beddoes's Pneumatic Institution in Bristol (1800), as did Coleridge, De Quincey and Tom Wedgwood (of Wedgwood China fame). soon ether frolics and laughing gas parties were the rage among the youth.

Itinerant medicine shows popularized ether and nitrous oxide administered through strange mechanical contraptions. Sam Colt, for instance, toured the wild west with six gaudy Indians and a nitrous tank, trying to make enough money to patent his new revolver - and before long, medical men got the message. A young dentist, Horace Wells, watched one of these nitrous stage shows and arranged through a colleague, William Morton, to demonstrate the gas in the classroom of the solemn surgeon John Collins Waren at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston (1844). Unfortunately, Wells did't know the proper amount of gas to give his burly patient, who writhed in agony when his tooth was pulled, and Wells was denounced with the scornful epithet "humbug!" But Dr. Charles Johnson suggested that ether, a more reliable substance, be used, and Morton worked to perfect a sponge inhaler that would administer steadier doses of it. In 1846, Morton returned to Warren's class and anesthetized a patient with ether so Warren could remove a tumor from the man's face. "Gentlemen," Warren gravely announced in the stunned silence that greeted the success of the operation, "this is no humbug."

Itinerant medicine shows popularized ether and nitrous oxide administered through strange mechanical contraptions. Sam Colt, for instance, toured the wild west with six gaudy Indians and a nitrous tank, trying to make enough money to patent his new revolver - and before long, medical men got the message. A young dentist, Horace Wells, watched one of these nitrous stage shows and arranged through a colleague, William Morton, to demonstrate the gas in the classroom of the solemn surgeon John Collins Waren at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston (1844). Unfortunately, Wells did't know the proper amount of gas to give his burly patient, who writhed in agony when his tooth was pulled, and Wells was denounced with the scornful epithet "humbug!" But Dr. Charles Johnson suggested that ether, a more reliable substance, be used, and Morton worked to perfect a sponge inhaler that would administer steadier doses of it. In 1846, Morton returned to Warren's class and anesthetized a patient with ether so Warren could remove a tumor from the man's face. "Gentlemen," Warren gravely announced in the stunned silence that greeted the success of the operation, "this is no humbug."

Indeed it was not. Everybody tried ether on the slightest excuse, and physicians vied with each other to discover other anesthetics. Sir James Young Simpson, a great Edinburgh obstetrician, gathered wife and friends around his dining table to sample lots of chemicals and found that chloroform worked more quickly than ether, so was more effective in relieving pains of childbirth. (Queen Victoria was delivered under chloroform.) Another famed Edinburgh teacher, Sir Robert Christison, head of the British Medical Association, self-experimented with coca, cannabis, opium, coniine, strychnine, and even extracts from the dread calabar ordeal bean of West Africa.

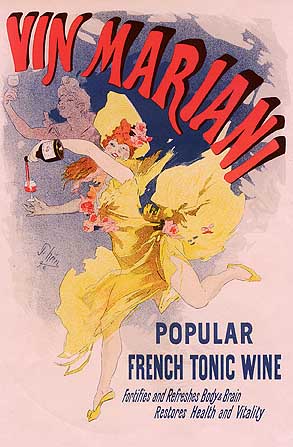

The last of the major plant alkaloids to be isolated in the nineteenth century was cocaine, by Albert Niemannn of Göttingen, about 1860. An enterprising chemist, Angelo Mariani, marketed a vastly popular coca wine and invented modern testimonaial advertising - sarah Bernhardt, Alphonse Mucha, Pope Leo XIII, Presidents Grant and McKinley, H.G. Wells and Thomas Edison were among the thousands who endorced the heady tonic.

Then, in 1884, young Sigmund Freud bought himself a gram of Merck cocaine ($1.27) and published Über Coca, a brilliant monograph that suggested the drug as an anesthetic and cure for morphinism. His friend Carl Koller demonstrated the use of cocaine as a local anesthetic for eye surgery a year later - a world shaking discovery that filled the newspapers and scientific journals for many months. IIt became part of every medical student's training to experiment with an infinite variety of drugs on himself, animals, patients, relatives, friends and then a whole new generation of students.

The last of the major plant alkaloids to be isolated in the nineteenth century was cocaine, by Albert Niemannn of Göttingen, about 1860. An enterprising chemist, Angelo Mariani, marketed a vastly popular coca wine and invented modern testimonaial advertising - sarah Bernhardt, Alphonse Mucha, Pope Leo XIII, Presidents Grant and McKinley, H.G. Wells and Thomas Edison were among the thousands who endorced the heady tonic.

Then, in 1884, young Sigmund Freud bought himself a gram of Merck cocaine ($1.27) and published Über Coca, a brilliant monograph that suggested the drug as an anesthetic and cure for morphinism. His friend Carl Koller demonstrated the use of cocaine as a local anesthetic for eye surgery a year later - a world shaking discovery that filled the newspapers and scientific journals for many months. IIt became part of every medical student's training to experiment with an infinite variety of drugs on himself, animals, patients, relatives, friends and then a whole new generation of students.

The world awakened with a new and panoramic consciousness; as medicine had once derived from magic, now it turned to scientific mysticism to explain the unearthly mental efects of the drugs. Wiliam James, who had giggled at laughing gas parties as a young man, spoke of the "anesthetic revelation" at Edinburgh in 1901, and the twentieth century was born.

Exploration of inner space with the techniques of modern science began. James was given peyote by S. Weir Mitchell, who had been experimenting with the cactus and mescaline since the 1880s. Investigation of peyote was the prototype for the contemporary study of hallucinogens, and with increased communications in scientific circles, researchers got to know each other's work more quickly. Heinrich Klüver's little classic, Mescal (1928), for instance, was read in 1936 by harvard student Richard Schultes, who switched from premed to botany because of it and took off to Oklahoma with anthropologist Weson La Barre to study Indian peyote rites. La Barre's book The Peyote Cult is now consulted as a guide to he old ways by Indian leaders; Schultes is now the foremost botanist of plant hallucinogens in the world, and his illustrator, Elmer W. Smith, provides the most accurate botanical drawings of drug plants in our time.

There were other strange connections. Koller established an eye clinic in New York, where he treated a ten-year-old boy suffering from severe astigmatism and myopa. Tthe boy was Chauncey Leake, who later in life organized the pharmacology lab at the University of California at San Francisco, out of which came divinyl ether for general anesthesia, amphetamines as central nervous system stimulants and nalorphine as a morphine antagonist. The discovery of amphetamine by Gordon Alles (1927) came about in the search for substitutes for ephedrine and epinephrine for asthma - research that had been going on since the days of Ko Hung. Alles also discovered the psychotropic effects of MDA, a synthetic closely related to the constituents of ordinairy nutmeg.

But the nineteenth-century explosion of drug use had gotten out of hand. Wiliam Halsted invented nerve-block anesthesia with cocaine (1885) but developed such a craving for the drug that his friends had to put him aboard a schooner for several months so he could kick the habit. He did, but became addicted to morphine from the ship's supplies. It was long a closely guarded secret at Johns Hopkins University that one of the institution's founders was a junkie. Halsted's student, James Leonard Corning, invented spinal anesthesia with cocaine.

Every family has a vicious drunkard dad or uncle on the loose; mournful mamas swigged patent medicines by the gallon; kids raised on heroin cough syrup graduated to coca-filled soft drinks.

Working girls took lunch breaks at Chinese opium dens, cocked-up blacks were impervious to bullets, teenagers puffed reefer and slaughtered whole families - at least according to the tabloids and police gazettes, where hese terrifying images of "dope fiends" first gained circulation. Prohibition fever gripped the land. Cantankerous reformers like Carrie Nation and pig-brained torpedos like Harry Anslinger seized the opportunity to enforce their dubious morality on the nation in the name of "stopping crime." Herion and cocaine were banned by the Harrison Narcotics act (1914); alcohol, by he Volstead act (1920-33); and pot, by the Marijuana Tax Act (1937). In a curious quirk of history, anthropologists and Indian leaders managed to save peyote from the general inquisition (1937), provided that its use was restricted to members of the Native American Church. Doctors were forbidden to presribe heroin even to addicts dying of withdrawal, and recreational drug use was driven underground.

The result was the creation, not prevention, of organized crime. Though many drugs vanished from the market shelves, they reappeared in the hands of crime czars only too happy to provide once cheap thrills for an inflated price. Fortunes were build on bathtub gin, Hollywood coke and New York smack. But prohibition proved impossible, as it always has. As liquor prohibition fell apart, jazz drifted up the river from New Orleans in a cloud of marijuana smoke, and black musicians were the cutting edge of contemperary civilization. Street dealers - Mezz Mezzrow and Detroid Red (MalcolmX) - grew into folk heroes, while Lady Day sang the blues. And lawmen hauled them away by the thousands.

World War II disrupted the natural flow of plant drugs, and substitute synthetics turned into nightmares of the fifties: Nazis on coke and methedrine and methadone, yankees on dexies and downers, housewives on tranks and businessmen back to booze. It seemed as though the world was going quietly mad in a gray flannel suit, unable to decide between Joe McCarthy and Marilyn Monroe. "I have seen the best minds of our generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, draggiing themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix," wrote Allen Ginsberg, and William Burroughs replied with the death knell of De Quincey's romanticism about narcotics: "I can feel the heat closing in, feel them out there making their moves setting up their devil doll stool pigeons, crooning over my spoon and dropper...."

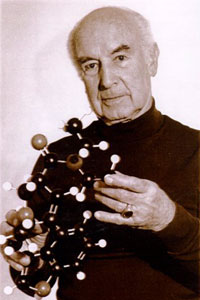

But in 1943 Albert Hofmann, a chemist investigating ergot derivatives at Sandoz Labs in Switzerland, had accidently absorbed some lycergic acid diethylamide through his fingertips. Suddenly the realms of altered consciousness predicted by James became available in mere microgram doses. Beneath the narcotized quiescence of the fifties bloomed a revolution. Scientists-philosofers rediscovered the magic halucinogens; Huxley and Osmond, Schultes and Hofmann, Wasson and Heim - a generation of seasoned Sufis devoted to new alchemy. At first this A-bomb of pharmacology, the most powerful hallucinogen the world had ever known, was hailed as a "psychotomimetic" - a fitting treatment for a schizophrenic world. Sure enough, LSD mimicked psychosis in clinical settings where doctors and patients expected it to. It is the nature of sorcerers' medicines to exaggerate the natural mind.

But in 1943 Albert Hofmann, a chemist investigating ergot derivatives at Sandoz Labs in Switzerland, had accidently absorbed some lycergic acid diethylamide through his fingertips. Suddenly the realms of altered consciousness predicted by James became available in mere microgram doses. Beneath the narcotized quiescence of the fifties bloomed a revolution. Scientists-philosofers rediscovered the magic halucinogens; Huxley and Osmond, Schultes and Hofmann, Wasson and Heim - a generation of seasoned Sufis devoted to new alchemy. At first this A-bomb of pharmacology, the most powerful hallucinogen the world had ever known, was hailed as a "psychotomimetic" - a fitting treatment for a schizophrenic world. Sure enough, LSD mimicked psychosis in clinical settings where doctors and patients expected it to. It is the nature of sorcerers' medicines to exaggerate the natural mind.

But in the lively information transfer of modern communications, nothing stays in the lab very long. Poets and artists who had long since learned about pot were ready for acid, and the psychologists gave it to them - in Prague, in Palo Alto, maybe even in Peking. The age of "psychedelics" dawned - with dozens, then thousands, then millions turning on. Kesey brought it out the mental wards; Leary and Alpert took it to Harvard, Ginsberg to India, Snyder to Japan. Distraught lawmen likewise tried to take prohibition worldwide, with treaties like the U.N. Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961) - an agreement made silly by he spectacle of nations like India promising to stop the use of prehistoric sacraments in 25 years. Stateside, omnibus drug bills collided head-on with the Merry Pranksters' magic bus, and both rolled into history the worse for wear. Age-old scenes recurred in modern guise; a whole army of Americans, like their French predecessors, tried pot and heroin in Vietnam.Coffee, cocaine, marijuana and heroin became the chief export crops of ancient psychedelic lands in Mexico and South America. Youth all over the world started growing its own weed and magic muschrooms. drugs once despised emerged resplendent in the middle class, and the "polydrug subculture" was a minority no more - if it ever was.

And what of the future? "Specific kinds of performance might be selectively enhanced by deliberate structuring of psychedelic-agent administration," wrote Willis Harman and james Fadiman with uncanny foresight in 1966. The sorcerers's skills of selection and technology will escalate the use of specific drugs for specific purposes: sometimes singly, sometimes combined, sometimes unwisely but sometimes ofering more education in an evening than in 20 years of school. Deadlier brain poisons lovelier love drugs than the modern mind can comprehend may rule the world. Already, hybrid chemicals like DOB and MMDA float through the minds of adventurous souls, work drugs, play drugs, body drugs, spirit drugs; there will be more, not less.

Alchemists will continue finding new and risky molecules. Use of plant drugs and derivatives, unceasing for three million years, will continue to blanket a schrinking world under the watchful eyes of communication satellites. Narcomaniac police will try to stop the inevitable. New worlds in far dimensions remain to be explored; we may greet strange forms of consciousness on some of them. Inner space meets outer space; a galactic exchange on untold planets intertwine. And it's good to be alive, in the morning of space time.

From: High Times Encyclopedia of Recreational Drugs, 1977 © THC Ministry Amsterdam 2005

Other pages on thc-ministry.net :

- PRESS RELEASE (March 24, 2004)

- Cannabis Religion

- Marijuana Religion

- Marijuana, The Untold Story

- Rev. Ferre's surfin habits

- THC Ministry Members

List of Other THC Ministry websites, look on this page for a THC Ministry in your area. - Donators

List of people and organisations who have donated to THC Ministry Amsterdam - Amsterdam Tourist information

Attractions and things to do in Amsterdam, recommended by the Amsterdam Cannabis Ministry - Exchange Links [1][2][3]

View who swapped links with thc-ministry.net - Forum Archives

- Members Artwork

- Search this site

- Downloads

- Cannabis Lawyer Database

Database for 'cannabis friendly' Lawyers, look on this page for a Lawyer in your area. - Contact